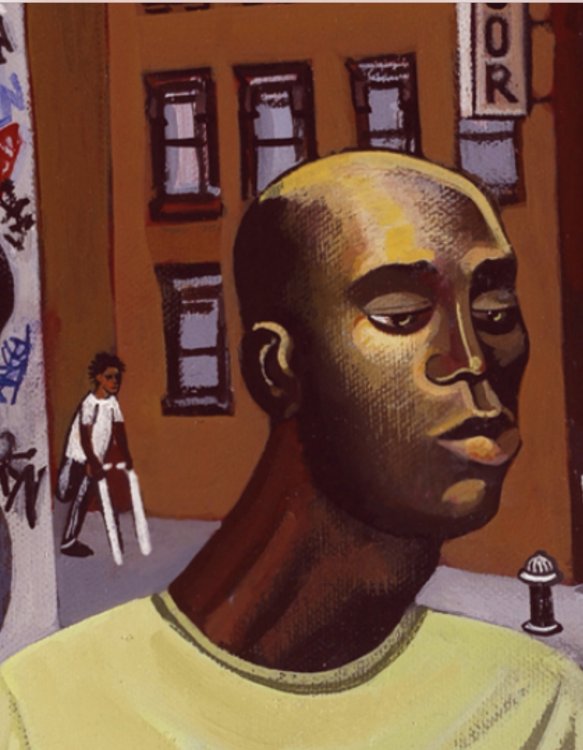

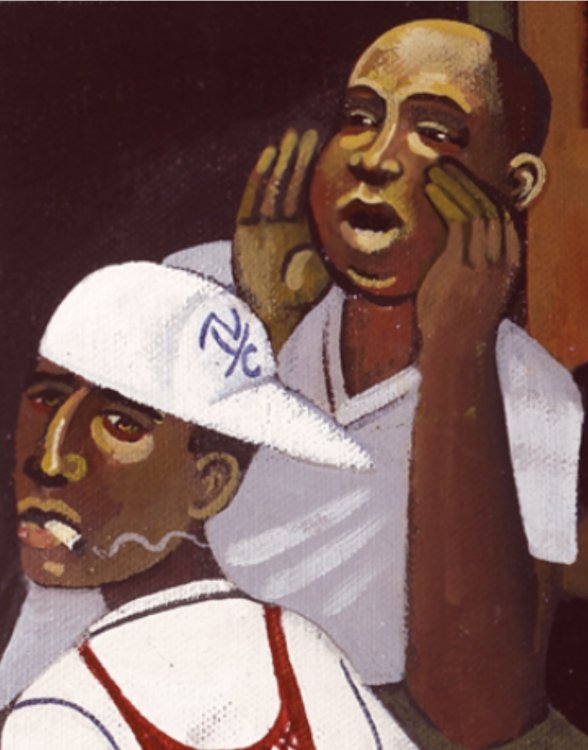

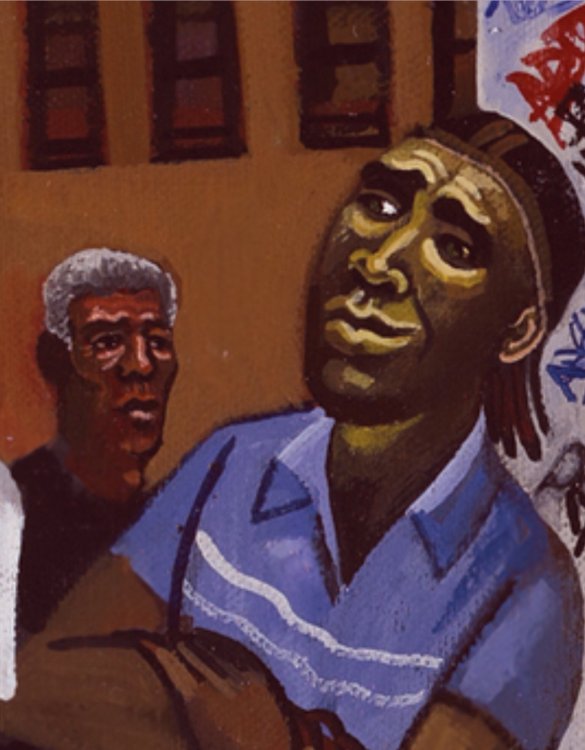

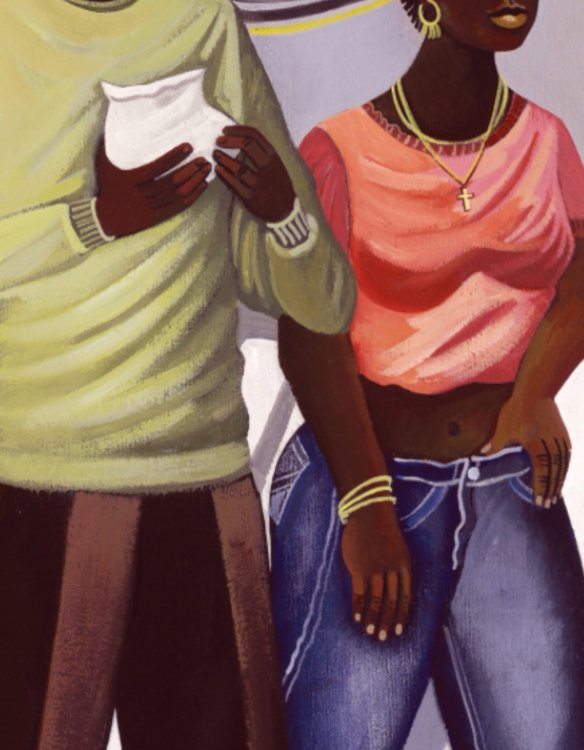

Harlem Crossing

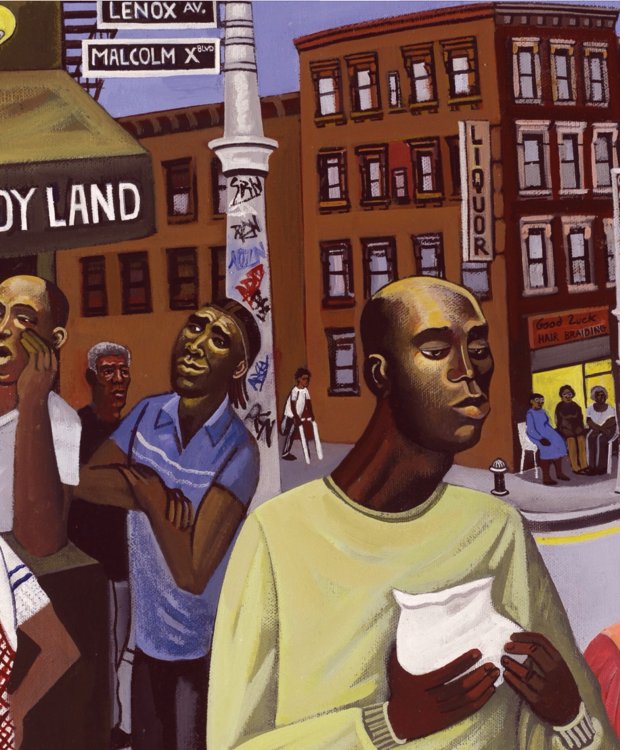

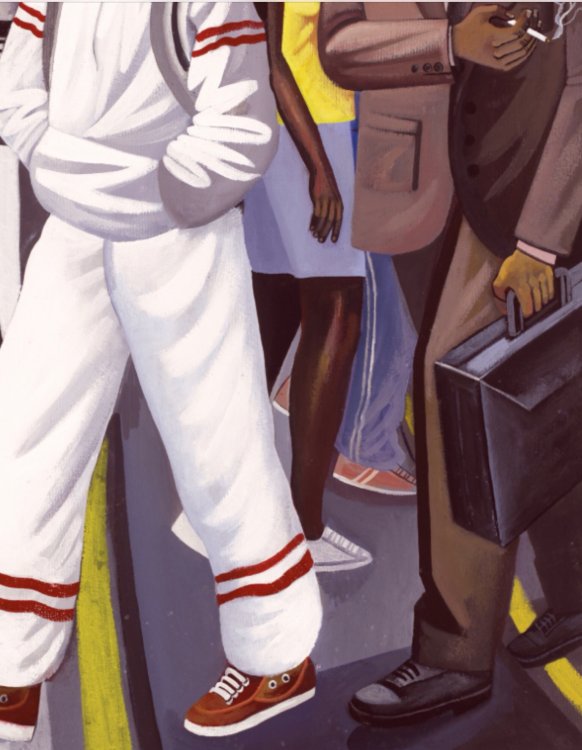

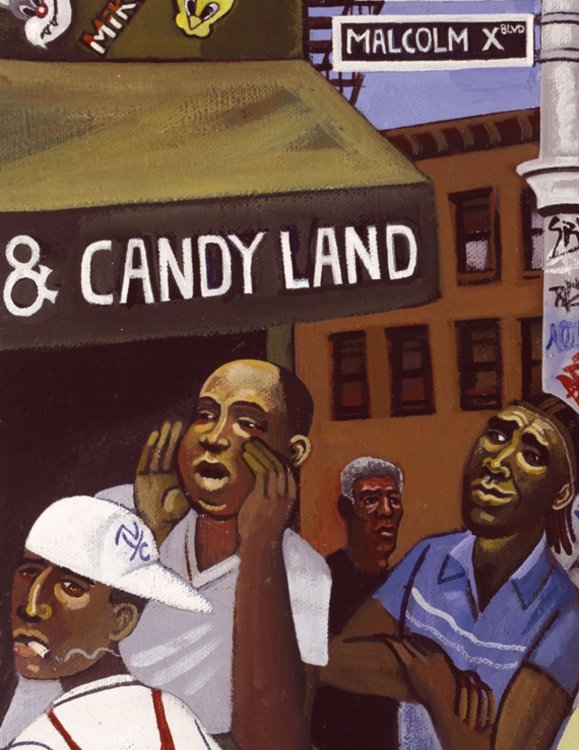

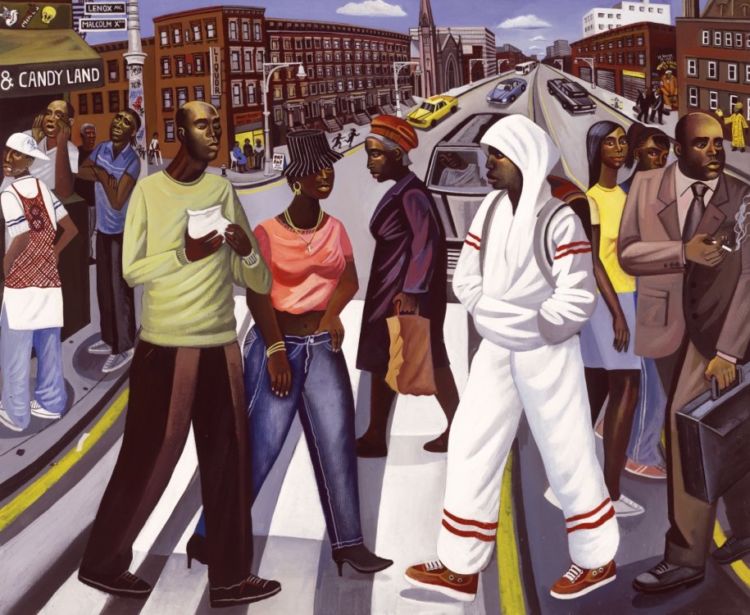

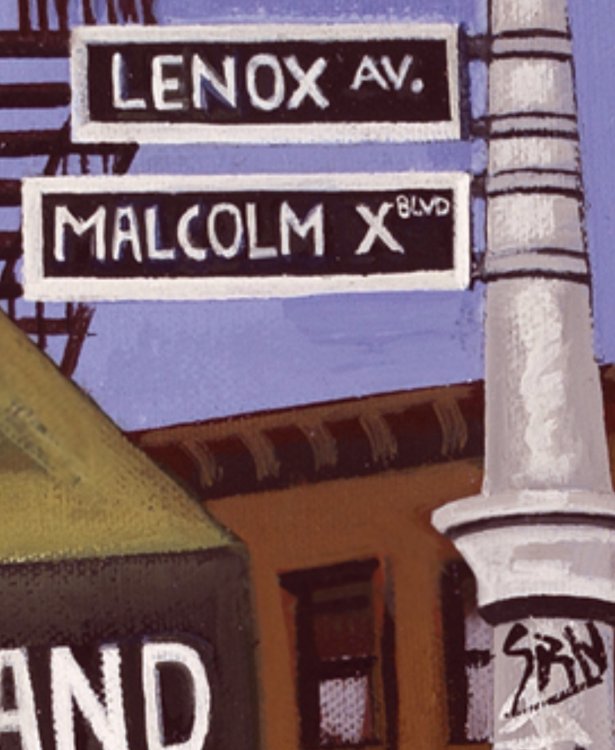

‘Harlem Shuffle’ Lenox Av and Malcom X Boulevard 2006

Boulevard of broken dreams

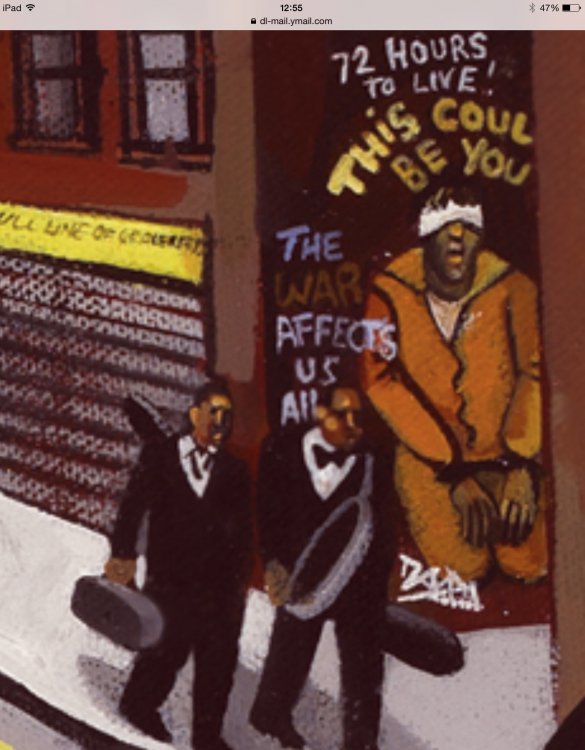

This week I wanted to shine a light on a painting I made in 2006 after a drawing trip to the streets of Harlem NYC. Several things made me think of this painting. I was reminded that May 19th is the birthday of the murdered Civil Rights leader Malcom X, a thought that was amplified by recent reading of a beautiful description of the streets of Harlem in James Baldwin’s 1962 novel ‘Another Country’. This led me on to think of Jacob Lawrence’s Great Migration 1940-1941 series of paintings in which he revisited the Harlem of his youth, newly populated with poor black migrants arriving from the South. Lawrence’s 60 panel pictorial narrative was painted in gouache on cardboard is among my favourite works of art. Harrowing and heartfelt but always full of humanity, Lawrence’s paintings reveal the narrowing horizons of the urban dream for migrants who had crossed the county to find jobs and relief from persecution and rural poverty https://lawrencemigration.phillipscollection.org/the-migration-series

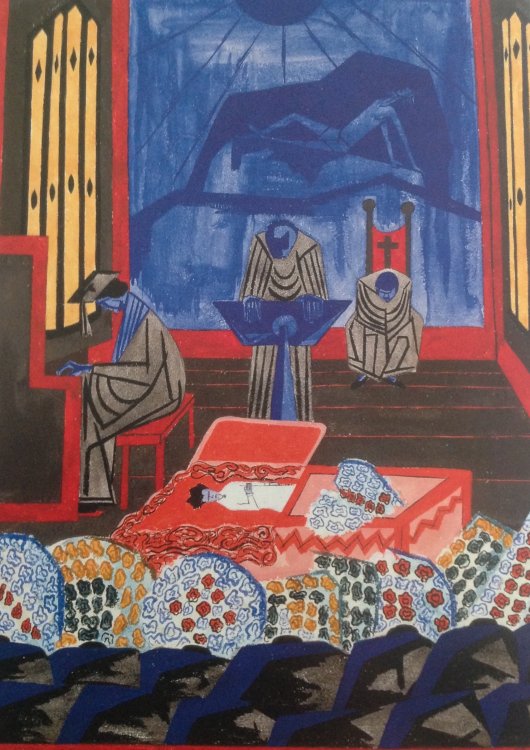

The painful reality Lawrence reveals is one of exploited workers living in disease ridden overcrowded tenements. Lawrence painted Funeral Sermon 1944 in memory of his own sister who died of tuberculosis in Harlem.

“We don’t have a physical slavery, but an economic slavery. If these people, who were so much worse off than the people today, could conquer their slavery, we can certainly do the same thing….I am not a politician. I’m an artist, just trying to do my part to bring this thing about” Jacob Lawrence

Funeral Sermon Jacob Lawrence 1944

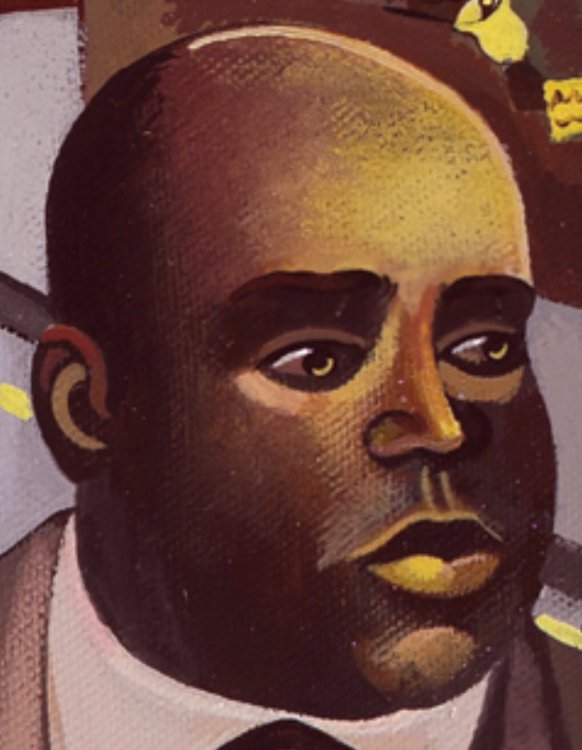

Jacob Lawrence 1917-2000

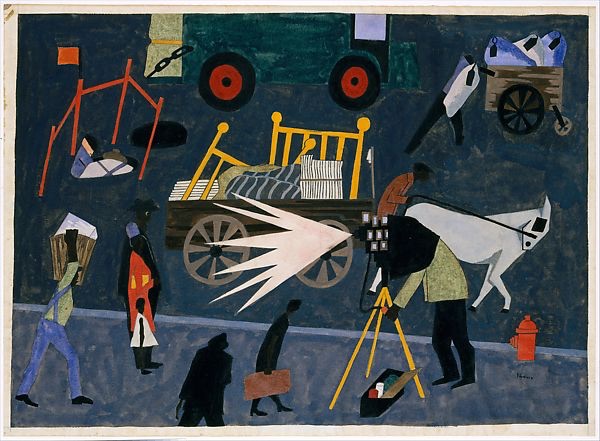

Harlem street photographer Jacob Lawrence 1942

Ascension: Illumination and revelation

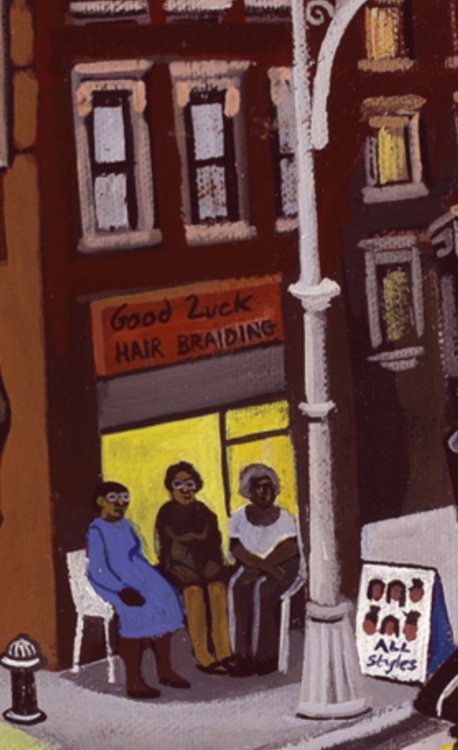

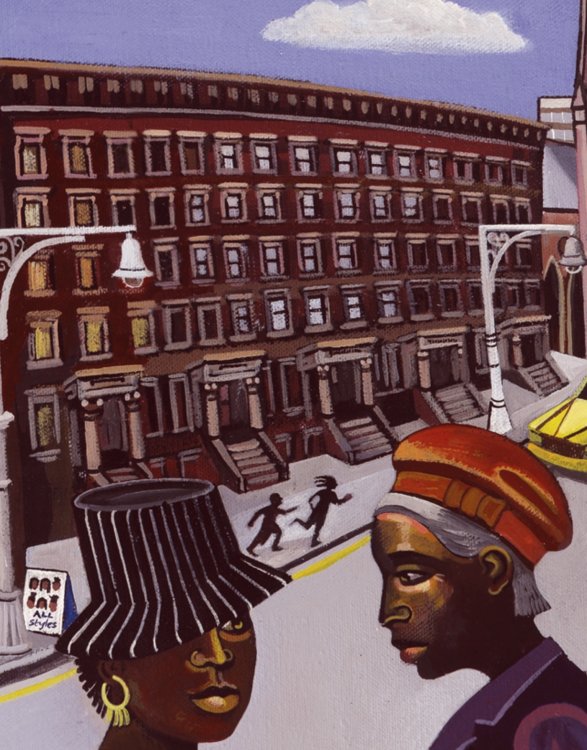

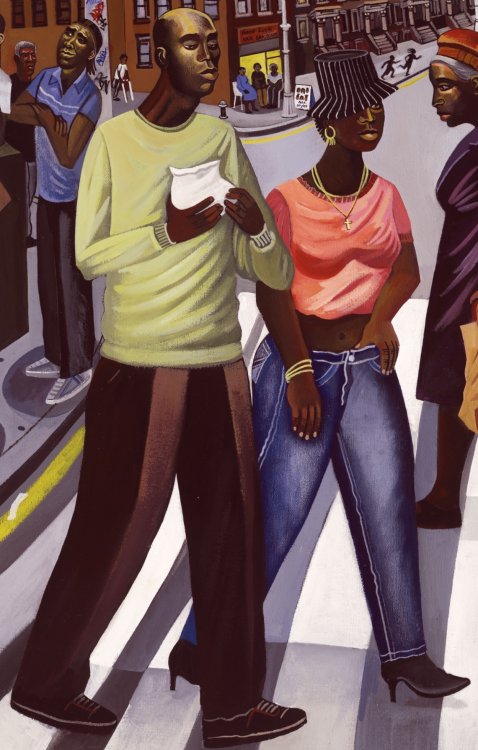

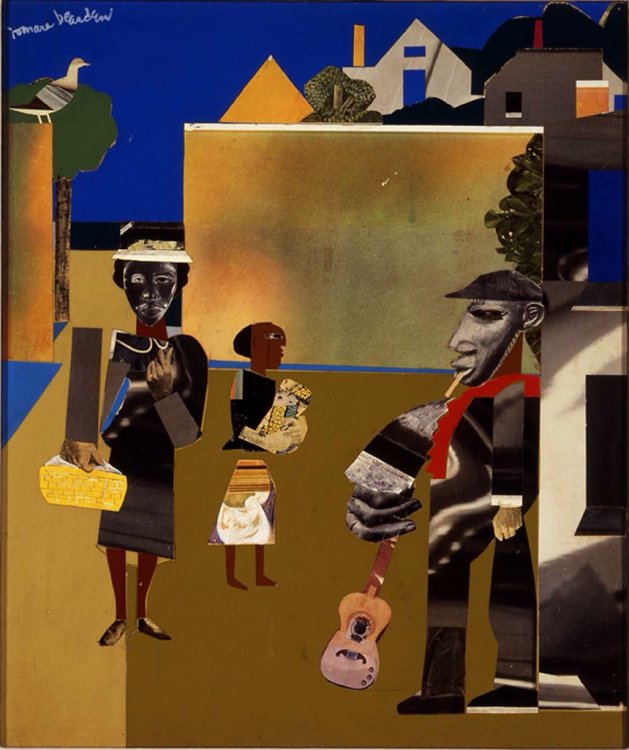

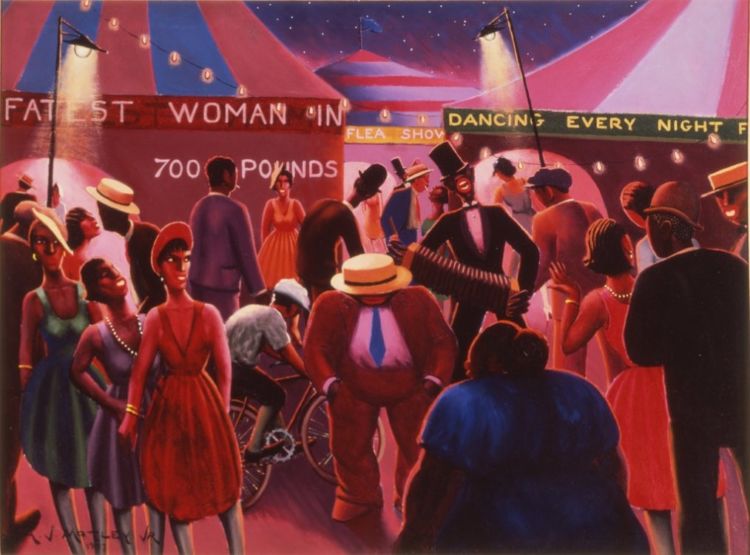

Despite this difficult start in life young Jacob Lawrence benefited from better the art educational opportunities he found in Harlem at the Utopia Children’s Centre, Charles Alston’s Harlem Art Workshop and Augusta Savage’s classes at the Harlem Community Art Centre. Here he discovered and built upon his love of painting which would eventually lead him to receive New Deal Federal Art Project commissions. Set up following the Depression the FAP boldly rekindled an art market made stagnant by the Depression, empowering artists regardless of perceived talent and stature. Lawrence’s Harlem series demonstrates the impact of the bustling streets on the young artist as he sought to illuminate the life around him. The FAP project was truly democratic in approach, inspiring ambitious public art that entrenched a sense of culture and shone a light on American life and values. It also gave badly needed income and sales to the 10000 artists involved. Another of the artists to benefit from the project was Romare Bearden whose boldly graphic depictions of black culture are strikingly beautiful. My own painting was made as a homage to these artists of the Harlem Renaissance that I love so much, Lawrence, Bearden, William H Johnson and Archibald Motley Junior.

Village Square 1969 Romare Bearden

Street Life in Harlem William H Johnson 1939

Carnival 1937 Archibald Motley Junior

Drumbeat heartbeat

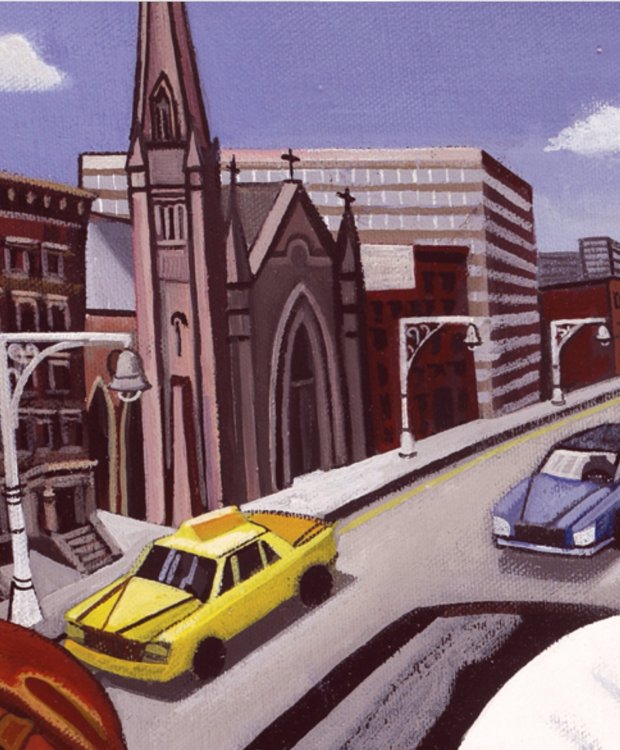

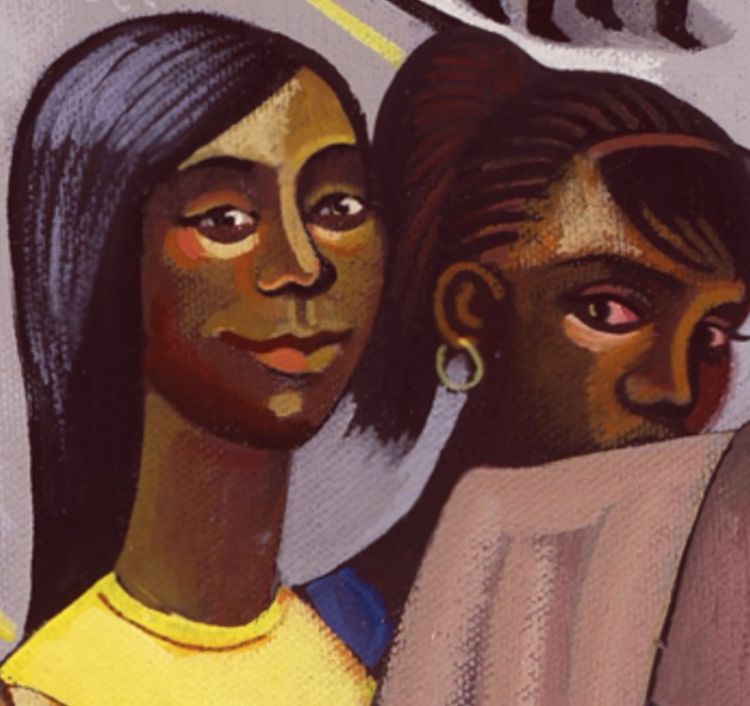

After walking the streets with my sketchbook I placed my viewpoint at a crossing I found along Lenox Av/ Malcom X Boulevard. Initially intrigued by the double street name, I hadn’t realised as I stood there sketching but I was at the centre of what had been the world of the Harlem Renaissance, the centre of the Jazz world in 1932, ‘Harlem’s Heartbeat’ as the poet Langston Hughes would have it in ‘Juke Box Love Song’,

I could take the Harlem night

and wrap around you,

Take the neon lights and make a crown,

Take the Lenox Avenue busses,

Taxis, subways,

And for your love song tone their rumble down.

Take Harlem’s heartbeat,

Make a drumbeat,

Put it on a record, let it whirl,

And while we listen to it play,

Dance with you till day—

Dance with you, my sweet brown Harlem girl

Blues and roots: A Little and a Lenox

The street was first named after the philanthropist James Lenox who used the wealth he inherited from his Scottish American merchant father to follow his passion as an art collector and bibliophile, establishing the Lenox Library, which became the New York Public Library in 1895, in addition to the New York Presbytarian Hospital. In 1855 Lenox was the third richest man in New York. By contrast Malcolm X was born Malcom Little. His father died while he was a boy, his mother was hospitalized and young Malcom spent his childhood in foster homes. In 1946 he was sent to prison for 10 years for larceny and breaking and entering where he became a Muslim, joined the Nation of Islam and changed his name to Malcolm X. He went on to become the public face of the organisattion, living a life under surveillance from the FBI. He left the Nation of Islam to embrace Sunni Islam and the civil rights movement, changing his name to el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz before his assassination in 1965. Three Nation of Islam members were convicted of his murder but suspicion continues to this day as to whether they were aided by law enforcement agencies.

Two names, two men with vastly different lives are linked in street names on one New York lamppost, two very different sides of New York City’s story, and yet there is a connection. The infrastructure of the merchant trade, the roots of Lenox’s grandfather’s fortune, depended at origin upon the labour of enslaved peoples. Generations of pain and rage, the scars of the slave trade, link these two men.

Another Country

Further on up the road the echoes of dienfranchised generations are still keenly felt in James Baldwin’s 1962 novel Another Country. Baldwin turns his sharp gaze onto a postwar Lenox Avenue in this excerpt,

“They had come out on Lenox Avenue….and nothing they passed was familiar, everything was wretched. It was not hard to imagine that horse carriages had once paraded proudly up this wide avenue and ladies and gentlemen, ribboned, beflowered, brocaded, plumed, had stepped down from their carriages to enter these houses which time and folly has so blasted and darkened. The cornices had once been new, had once gleamed as brightly as now they sulked in shame, all tarnished and despised. The doors had not always brought to mind the distrust and secrecy of a city long besieged. At one time people had cared about these houses; they had been proud to walk on this avenue, it had once been home, whereas now it was a prison. Now no one cared, this indifference was all that joined this ghetto to the mainland. now everything was falling down and owners didn’t care, no one cared. The beautiful children in the street , blue-black, brown and copper all with a grey ash on their faces and legs from the cold wind, like the faint coating of frost on a window or a flower, didn’t seem to care that no one saw their beauty.”

As as I stood sketching in 2006 at the crossing, watching the flow of people and the rhythms of their feet, I was thinking all the Jazz music, art and literature that has been such a part of my life that was born here in Harlem. The vibrancy of the art that came from these streets is filled with the optimism of people celebrating black identity. Harlem has risen and fallen so many times throughout its history. If I were to go back today and sketch again at this crossing that painting would be one that depicts a more diverse population. My painting is of a moment when Harlem was in the process of gentrified change, a Harlem crossing from one direction to another, towards yet another unknown country.