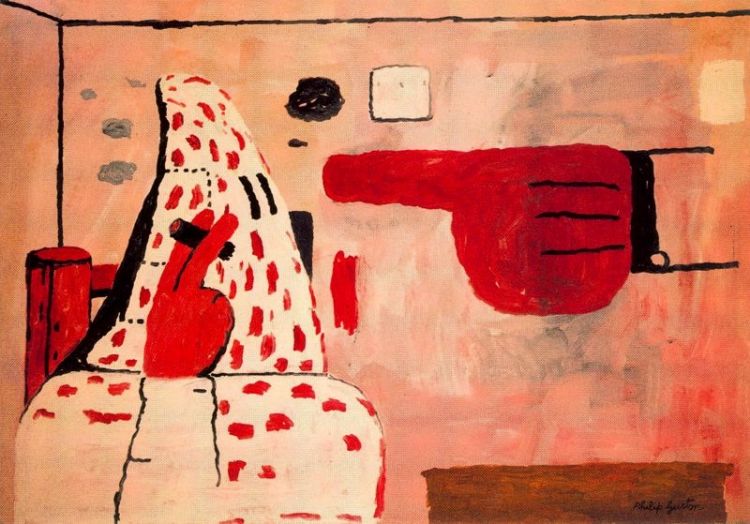

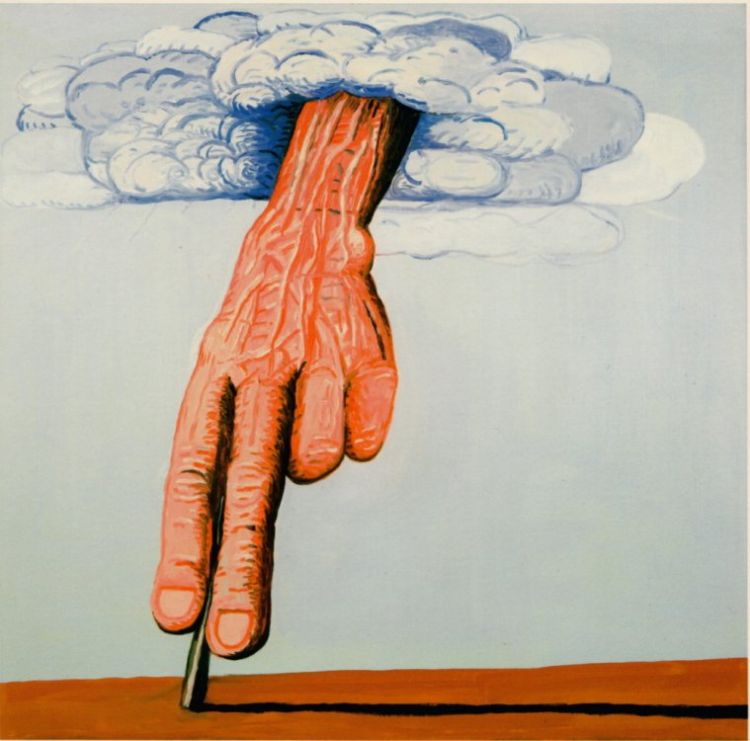

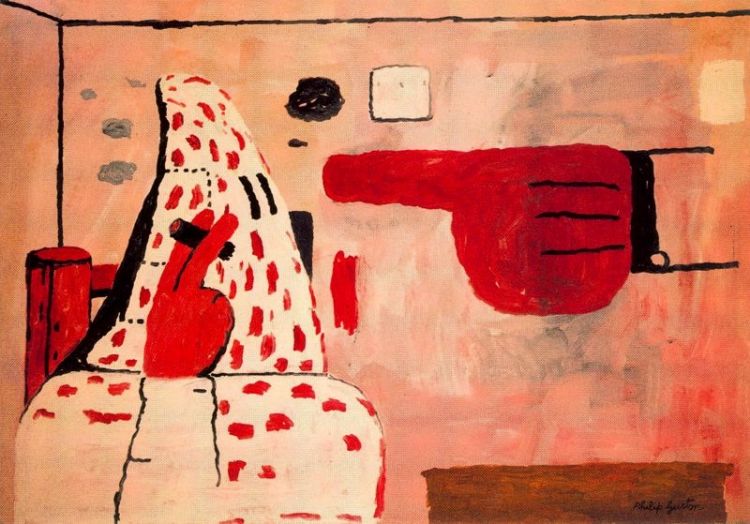

Philip Guston ‘Arm’ 1979 Oil on canvas 121.9 x 152.4 cm

‘My whole life seems just a long falling’ John Updike from ‘Couples’ 1968

Frozen

Frieze Art Fair 2019 Regent’s Park London and one painting sucks in the air around it, drawing you in, freezing you as you stand before it.

Whose arm is this?

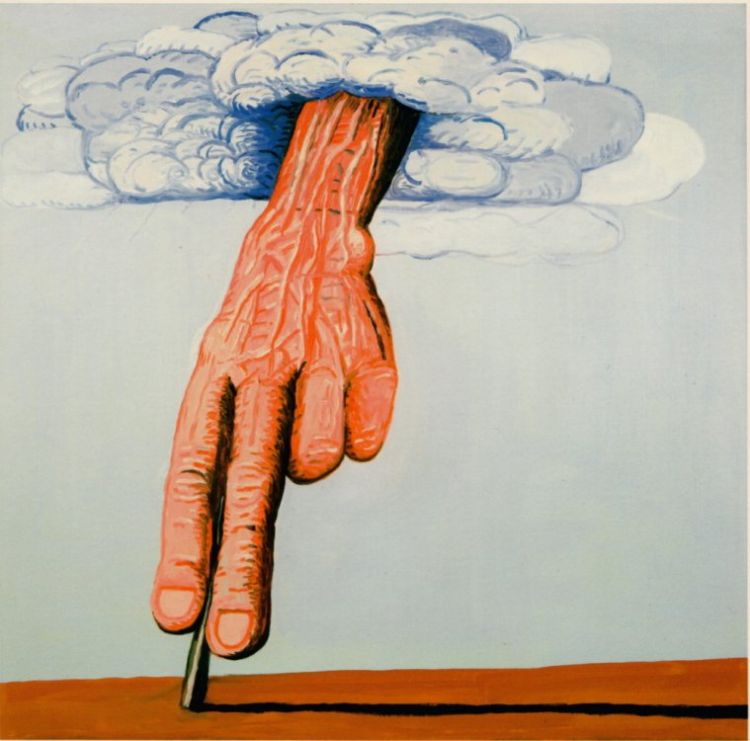

A priest’s hand lowered in gesture? The hand of an almighty creator- Prometheus or Michelangelo’s Sistine touch of God giving life to Adam- or the hand of an artist creator, a painter’s hand?

Michelangelo Adam and God fresco detail from The Sistine Chapel 1512

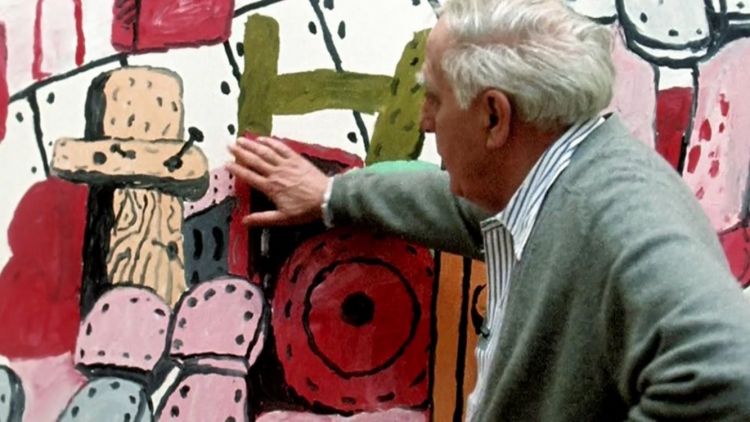

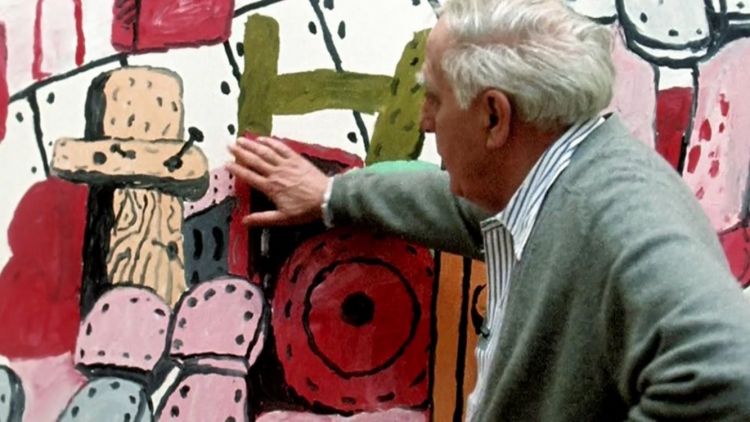

Philip Guston 1913-1980

Could Guston’s phantom limb be the arm of a shadowy gangster or a politician giving their blessing to an order for retribution? An arm lowered in submission or salute to a doctrine of genocide?

Is it a fall from grace? Icarus overreaching and plummeting to earth, his dreams melting around him. Maybe we are looking at a man jumping from an internal existential crisis, fleeing a deluge, flailing as his life flashes before him, suddenly imbalanced and grasping into the void for a faith that he knows is nowhere? A sudden revelation of long-buried truth. Is it an empty hand with nothing left to offer?

Is this the arm of a man jumping in terror from an external act of unimaginable global barbarism as a last act of free will and defiance? Or maybe it is just a dream, a falling asleep, a falling in love, a letting go, a release or an open handed unfurling from this mortal coil.

In the Claw

Hand over $5M to Hauser and Wirth and you can buy this moment. But what moment is it that are you really buying with your dollars?

According to the art critic Hilton Cramer writing in the New York Times in 1970 about Guston’s rejection of his status as chieftan to the tribe of abstract expressionists in a sensational stylistic shift to autobiographical symbolism, you are buying into a ‘pseudo event’ of cartoon anecdotage. In making his new works Guston was ‘donning the mask of a Stumblebum’ (‘A Mandarin Pretending to Be A Stumblebum’ Hilton Kramer, New York Times October 25 1970). Guston’s own reasons for this reawakening are well documented,

‘American Abstract art is a lie, a sham, a cover-up for a poverty of the spirit. A mask to mask the fear of revealing oneself. Where are the wooden floors- the light bulbs – the cigarette smoke?’

And later still

‘I was feeling split, schizophrenic. The war, what was happening in America, the brutality of the world…What kind of man was I, sitting at home reading the magazines, going into frustrated fury about everything and then going back into the studio to adjust a red to a blue’.

‘Stumblebum’ is the language of the Republican right- it is a badge of failure and nonconformity, a label to pin on societal misfits.’Mandarin’ is a cheap pop at Guston’s sphere of influence over his leftist cabal. Hilton speaks for the establishment when he writes his review and in doing so he points directly at the all reasons why you have yourself a bargain if you buy Guston’s ‘Arm’ for $5M. Give that man a big hand.

Philip Guston. Courtroom, 1970; Oil on canvas, 67 x 129 in.

Hoods in your ‘Hood

Put on your sleep-mask and let’s enter the dreamscape of a master myth-maker.

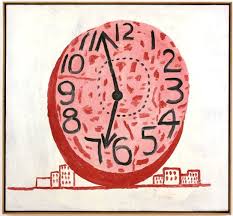

Guston’s world is peopled with ‘hoods’. As Kramer wisecracks in his NYT article Guston certainly ‘dons a hood’ or two. In his paintings the omnipresent artist figure wears a hood as he works at his easel, puffing away on a cigarette, measuring his days in fag butts and clock-ticks and silently assenting to society’s oppressors. We all don masks when we have to and that’s the point. We need to mask our emotions sometimes to avoid scrutiny and the appearance that we are all failing through the wide blue sky, jumping into our unknowable futures. As children we come to understand slowly the shocking reality of death and the tick-tock of life that beats in our chest and we learn to mask the fear that our own clock will stop one day. We create meaning where there may be none. We believe in religion, art, money, we follow our teams, we play the game and sing the song, we raise a glass and wink an eye.

Stepping over bodies in the street or tuning out the news of constant war or being deafened by the doublethink of modern politics, it seems easier not to listen sometimes. Muffle your ears and blinker your eyes, the circus is too distracting. That’s when the symbolism of the moment slips past unnoticed and silently, swiftly, the script changes. Language is legitimised, scapegoats demonised, the Hoods are out of the shadows and in your streets in broad daylight and all hell breaks loose. Guston won’t let this happen though. He can’t. He’s seen too many tears and heard too many cries from the condemned in the hands of the complicit and felt the weight of the silence that follows.

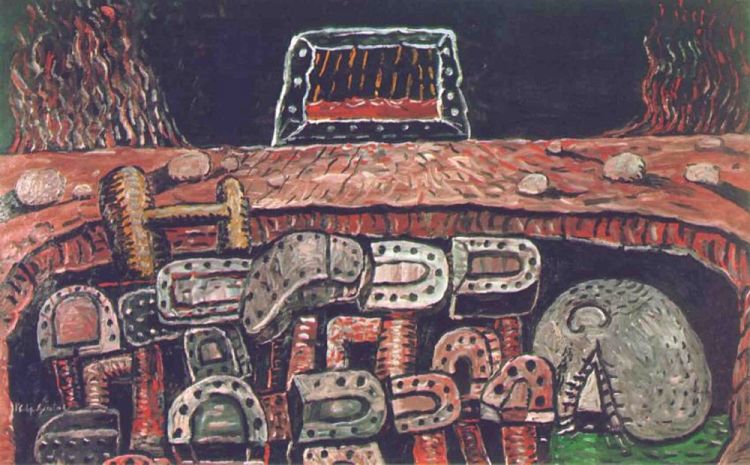

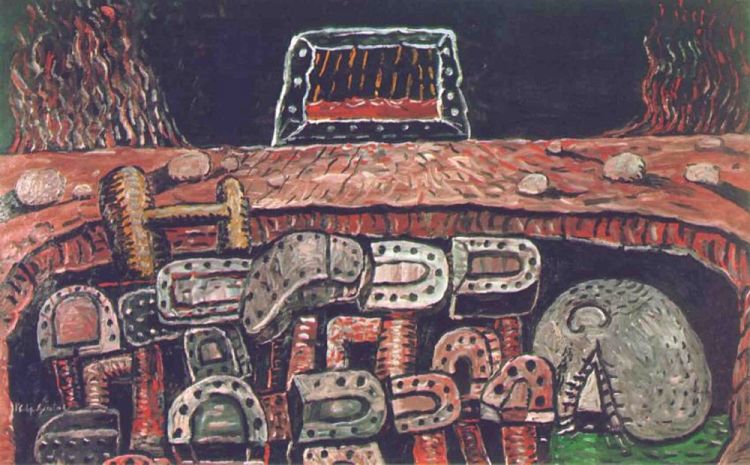

Lower Level 1975 Oil on canvas 171cm x 185cm

Give ‘Em Enough Rope

Young Philip Goldstein was the son of Jewish immigrants from Odessa who had escaped persecution in Ukraine fleeing to Canada in search of a better life. They settled in a Jewish ghetto in Montreal, moving to the warmer climes of LA a few years later where his father Louis, a blacksmith, could only find work as a junkman collecting refuse in a horse-drawn wagon. The traumatic strain of migration, antisemitism and poverty and was too much for Louis. Depression settled over him until he tragically took his own life.10 year old Guston, now renamed to fit into his new life, found his father’s body hanging from a rope thrown over the rafter of a shed.

Slaughter In The Dark

The pain is still there when you lay down to sleep. The fear is still there when the lights go out. The blood sweat and tears of an immigrant father, a man out of his depth, his inexplicably empty worker’s boots worn so thin that the nails spike through. Later still the hushed murmurings of relatives abroad in Jewish ghettos and prison camps. Piles of shoes in the dark. Six million dreams never dreamt and all those footsteps never taken.

Painting Smoking Eating 1973

Pit 1976

Some Very Fine People

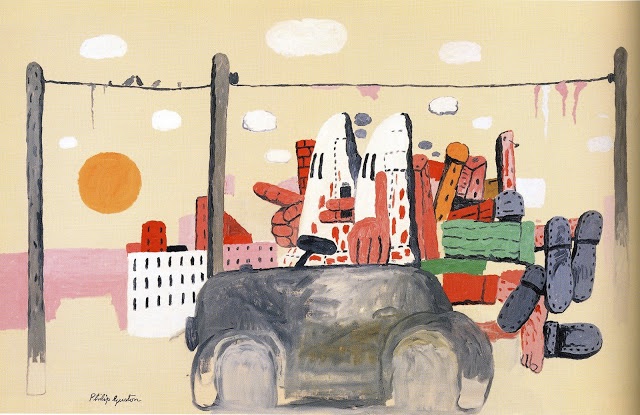

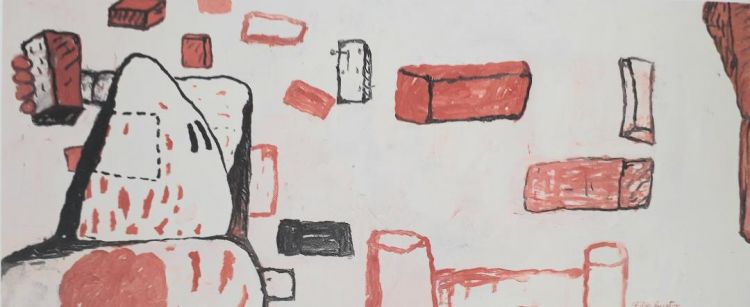

Guston can’t forget the past and he will hit you over the head with a symbol over and over again if you enter his world. The same cloth-ears and blinkers are the uniform of Guston’s Ku Klux Klan hoodlums, issuing orders and carrying out operations at dawn with wooden crosses and the dead sticking out of the back of their wheel-less car. It is the chilling urban drudge work of the despotic state depicted in grotesque cartoon mimicry. The banal bureaucracy of genocide that you can ignore until the knock comes to your door. This is Kafka, Orwell, Beckett and Pinter on canvas. It’s the chant of the re-education camp classroom and the unseen hands smothering journalistic truth in a pillow case of ‘fake news’. But the ‘hoods’ are afraid too and their President is a bollock-headed sick man with a phallic nose, rotting away in office, dragging a phlebitic leg and dripping with shame. Fear builds walls that brick you in. Fear eats the soul.

“The wonder of Nixon (and contemporary America) is that a man so transparently fraudulent, if not on the edge of mental disorder, could ever have won the confidence and approval of a people who generally require at least little something of the ‘human touch’ in their leaders.” Philip Roth 1971

“You had many people in that group other than neo-Nazis and white nationalists. The press has treated them absolutely unfairly. You also had some very fine people on both sides”

President Donald Trump speaking after the Unite the Right March in Charlottesville 2017 in which a car driven by a white nationalist was used to attack a crowd who were protesting peacefully against the march, killing Heather Heyer and injuring 28 other people.

Philip Guston Dawn, 1970 Oil on canvas 67 x 108 inches

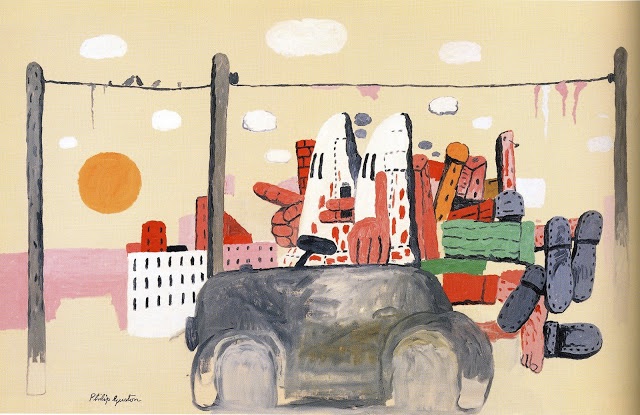

Central Avenue 1969

San Clemente 1971

Scared Stiff 1970

“You are Josef K.,” said the priest, and raised his hand from the balustrade to make a gesture whose meaning was unclear. “Yes,” said K., he considered how freely he had always given his name in the past, for some time now it had been a burden to him, now there were people who knew his name whom he had never seen before, it had been so nice first to introduce yourself and only then for people to know who you were” Franz Kafka ‘The Trial’ 1915

Here is Guston’s ‘Arm’ found in The Trial by Kafka, a complicit priest’s arm lowered in gesture.There is that oppressor, that gangster, that politician that will steal your name and make you forge a new identity so that you fit the mould, cooperate with investigations and don the hood. If you can’t beat ’em….. Anything to escape the fear.

“Why are they going to disappear him?’

‘I don’t know.’ It doesn’t make sense. It isn’t even good grammar.”

Joseph Heller, Catch-22 1961

Forging Armour

The Studio 1979

Stamped with a new name and forged by all the torments that had befallen him the young Guston created a new identity, an armour against all the missiles the world seemed to be hurling in his direction. The story goes that he hid himself away in a cupboard beneath a bare light bulb (cartoon-speak for ‘Epiphany!’) and drew. Bulbs would become a dual symbol life and death in Guston’s visual lexicon.The light bulb that represents the glow of inspiration and enlightenment is interchanged with the shape of a noose with all its dangling flexes and pull-chords: lights out, life extinguished.

Art was to be Guston’s salvation then, particularly the renaissance works of Piero De La Francesca and Masaccio. The graphic compositions and beautiful blues, pale reds and pinks of Guston’s paintings are evidence of his endless copy-taking from the old master painters that he loved all his life. About Piero he wrote,

“…without our familiar passions, he is like a visitor to earth, reflecting on distances, gravity and the positions of essential forms…You see a tree, angels, some ground, a little bit of water, some reflections, sky, clouds, hills, limbs. It’s as if he came down and opened his eyes up for the first time. It has that feeling. I want to do that. I want to paint the world as if it had never been seen before..maybe I have to go through this whole torturous business to do it.”

Piero Della Francesca ‘Battle between Heraclius and Chosroes’ 1452-66 Fresco, 329 x 747 cm San Francesco, Arezzo

Detail from Piero Della Francesca’s ‘Battle between Heraclius and Chosroes’ 1452-66

Plain 1979 175.3 x 236.2cm

The Line 1978 Oil on canvas 180cm × 186cm

Dreamcatcher

Guston took great strength from the renaissance painters, Piero Della francesca, Ucello and Masaccio, building their forms and structures into his paintings alongside their feeling for mystery and wonder. These great painters sustained him throughout his life, as we can see from this letter to the artist Mercedes Matter written in 1975,

‘….I’ve never felt more remote from what’s called “Modern art”. What a fabulous source of inspiration the past is! I feel like i’ve made- travelled over- a vast circle- when I was a boy of 17 or so, all I could look at was Piero, Masaccio, and other later masters, and here I am back again for the last ten years or so, but with greater intensity and in a renewed alive way. …when I am faced with an Italian master work, I am put deeply in a state of anxiety, almost painful and ecstatic at once- their particular-special, rare mixture of the ideal- the optimum order, going together with the “human”, the observed tangibilities of life. I think finally it possesses the aspects of a dream – a plastic dream – and this strangeness is what makes me feel so faint’.

Suffering Nails and Arrows

In the same letter Guston addresses his fears in one of the most honest, precise and moving accounts of an artist suffering the slings and arrows of self doubt ever written. As ever, Guston nails it,

‘….Of course it is all internal, private and silent. All having to do with painting- creating, overwhelming self-doubt in spite of the fact that I’ve never painted so much as I have this year. I try desperately to put everything aside in order to concentrate, which is to say TO LIVE THE PAINTING- what a difficult state of being to move into it is totally another way of life than what we are accustomed to ordinarily! And yet, if I have one good day in ten I am fortunate- the rest is torment and a shambles- and debilitating self torture and disgust. After so many years of work I feel I know nothing at all – so very little – in front of the canvas or the drawing paper. I feel like an innocent- a beginner- a primitive. Also there is the anxiety- a fierce one- of time- a dominating feeling of getting old puts me in the worst depressive states I’ve ever been in. I know this isn’t unique- I know. Yet experiencing life, to oneself, in oneself, has nothing to do with knowing or rationalising it all.’

Bulbs and Bricks

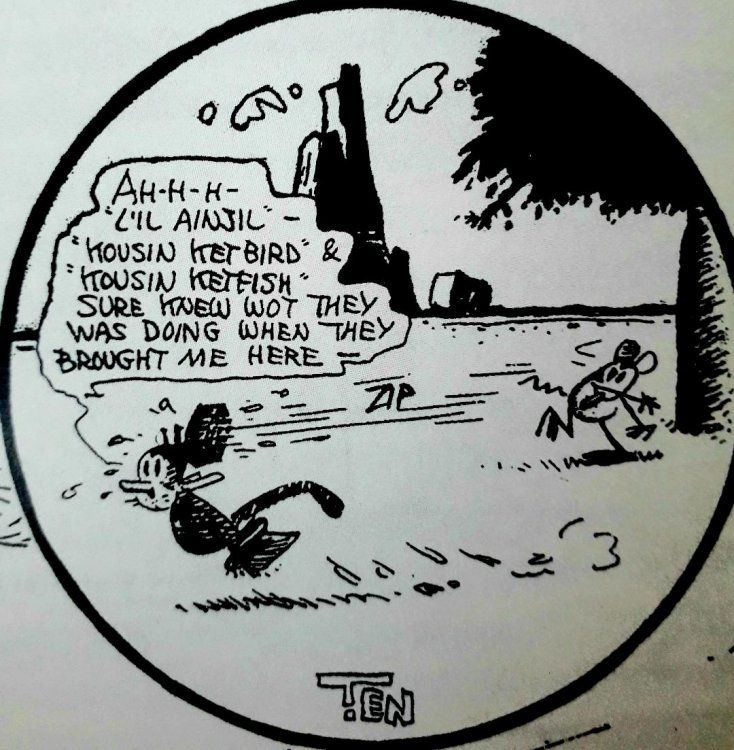

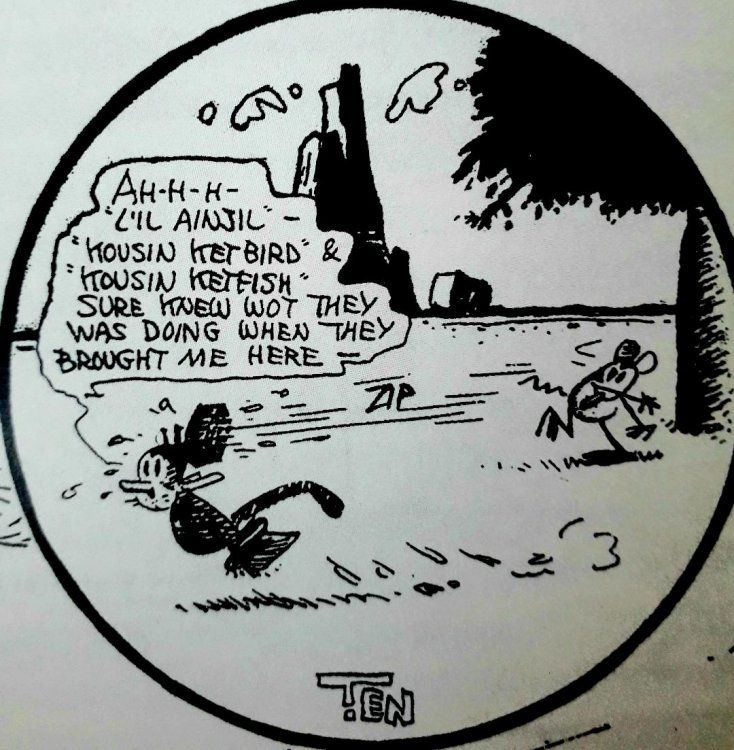

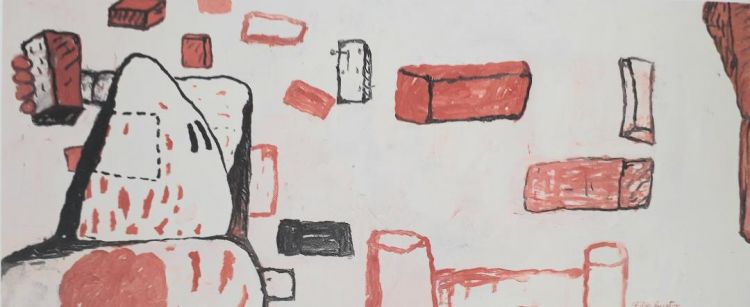

Propagating under the light bulb inside his cupboard Guston was also studying the work of LA based cartoonist George Herriman. Herriman was born in New Orleans in 1880 to mixed race creole parents. His Krazy Kat cartoons centred on a love triangle between Ignatz Mouse, Kraz Kat and Offisa Pup in which Ignatz chucked bricks at Krazy which the naïve androgynous Kat then interpreted as symbols of love. Pupp made it his mission to prevent Ignatz from throwing bricks at Krazy, or to jail him for having done so, but his efforts were perpetually impeded because Krazy wished to be struck by Ignatz’s bricks. Herriman’s genius was to create cartoon as rhythmical as New Orleans jazz, possessing a simple conceit that brilliantly exposes human weaknesses whilst simultaneously celebrating the power of free will and civil authority’s need to curtail the unorthodox. Here was a chaotic imaginary world that must have struck the young Guston as one filled with glorious insight into the human condition. As Krazy says in this excerpt, just as another brick zips into his head, ‘They sure knew what they was doing when they brought me here’. That could be Guston’s mantra.

Krazy Kat cartoon detail, George Herriman 1922

Bricks 1970

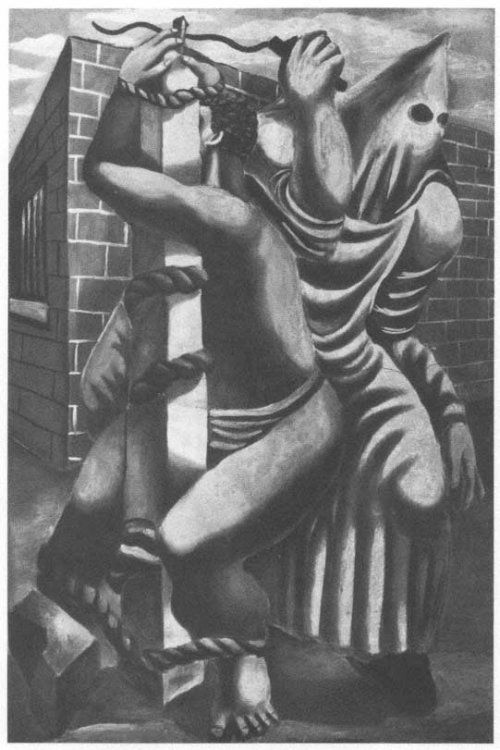

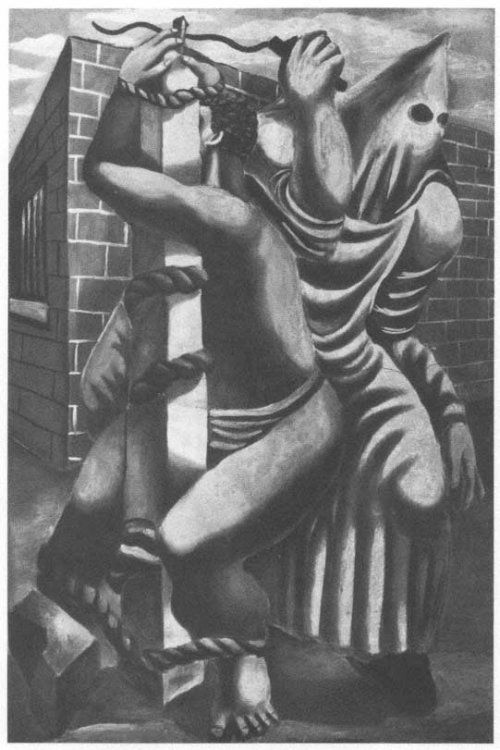

Striking Back at the Invisible Empire

An episode of from Guston’s attendance at Manual Arts High School stands out as an early example of activism. Guston and his friend Jackson Pollock were both expelled for distributing leaflets against the popularity of high school sports. The ‘jock’ is a revered symbol of conformity within the High School establishment, a stereotypical image of anti-intellectual all American male-hood. Guston had taken aim at the establishment. After departing college he supports himself as an odd job man in a sea of union and anti-union power struggles The Ku Klux Klan, or Invisible Empire, were helping to break these strikes remembers Guston,

‘The police department had what they called the Red Squad, the main purpose of which was to break up any attempts at unionizing…The KKK helped in strike breaking so I did a whole series of paintings on the KKK. In fact I had a show of them in a bookshop in Hollywood, where I was working at that time. Some members of the Klan walked in, took the paintings off the wall and slashed them. Two were mutilated. That was the beginning.’

The image of the KKK hood took hold and was reinforced in a mural about the Scotsboro Case where nine black men accused of the rape of a white woman were sentenced on circumstantial evidence and trumped up charges. Unidentified vandals attacked these murals. Guston now had the symbol that would haunt his paintings to such powerful effect from now on.

Mural panel 1933

Sinister Bends

In 1935 Guston received funding via the mural section of the Federal Arts Project, part of Roosevelt’s New Deal via the Works Progress Administration. His interest in murals was further fuelled by pilgrimages to view the Diego Rivera murals in the LA region and to Dartmouth in 1937 to see the Orozco murals, followed by a trip to Mexico to work with the great Mexican painter David Alfaro Siquerios in 1934. Although short lived this experience was central to Guston’s development as an artist. In Mexico he had found a society that freely encouraged artists and enabled them to create political public works on a grand scale.

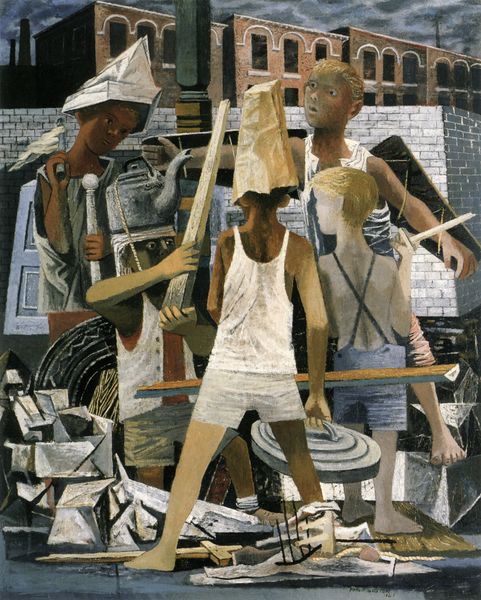

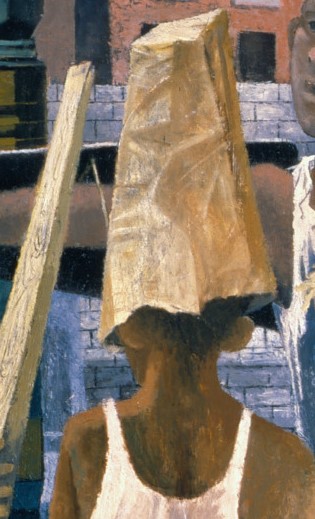

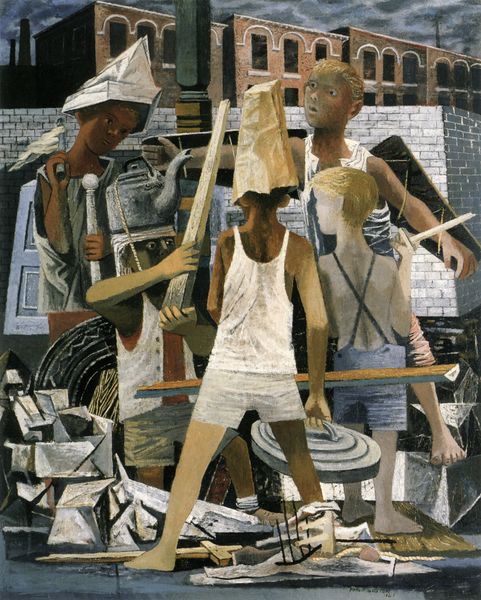

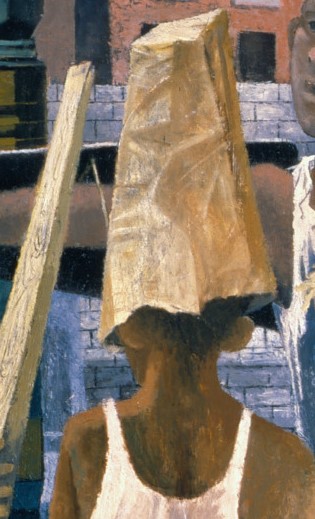

His subsequent painting Martial Memory from 1941 is a painting that owes so much to Piero Della Francesca. Diguisary and role play fill the picture plane. Guston has always been interested in identities, hidden and invented. here we are introduced to the dustbin lid shield and the tinpot helmet. In the imagination of the street the possibilities for reinvention are endless. But this is 1941 and the forces of fascism are burning Europe and Europeans. Suddenly the war games and crude weaponry bend darkly before us, innocence is shattered. A paper bag hood is centre frame.

Martial Memory 1941

Detail from Martial Memory 1941

Before the Flood

Further echoes of the military mask symbol appear in this scene from Guston’s commission to document the Naval Air Corps in 1942. The semi submerged soldiers in Clothes inflation Drill could be putting on Guston-hoods as they prepare themselves against the bullets and bombs to come with flimsy cloth and the thin air of their own breath, just trying to keep afloat.

Clothes inflation drill 1941

“They’re trying to kill me,” Yossarian told him calmly. “No one’s trying to kill you,” Clevinger cried.

“Then why are they shooting at me?” Yossarian asked. “They’re shooting at everyone,” Clevinger answered. “They’re trying to kill everyone.”

And what difference does that make?

Joseph Heller, Catch 22 1961

Deluge

Symbols and themes reoccur, re-amplifying and redacting throughout Guston’s career until just the essential elements are left. Guston’s paintings of 1979 can clearly be viewed metaphorically as images of an America awash with the fallout from the Vietnam war, assassinations, racial tensions and the Nixon presidency and resignations of the late 1960s and 70s. The soldiers at drill in 1941 were trying to stay alive, now Guston gives us humanity drowning in a bloody pink sea. This could be the Mediterranean today, another doomed migration of desperate people escaping poverty or the fallout from incomprehensible wars that they had nothing to do with.

Sea Group 1979

Red Sea, The Swell, Blue Light 73 in. x 237 1/2 in.

Shelter from the Storm

Love provides the only sanctuary as the figure of the artist and his lover cling tenderly in their silent embrace, masked by sleep and forever hiding together under sheets. We feel the vibrations of their trembling bodies, his brushes quivering like arrows as he holds on tight to his partner, his beloved fellow artist, muralist and poet Musa McKim Guston.

Couple in Bed 1977 Oil on canvas 206.2 × 240.3 cm

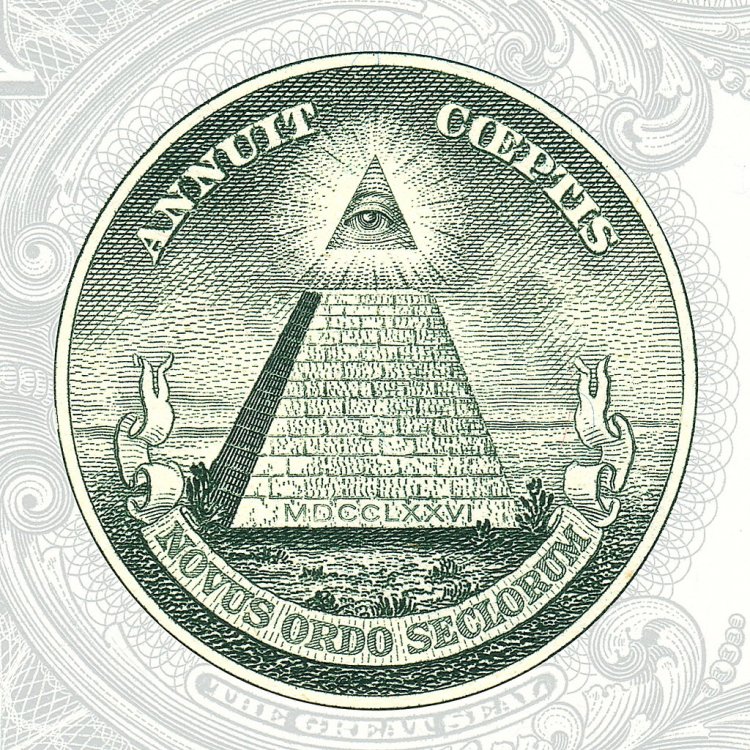

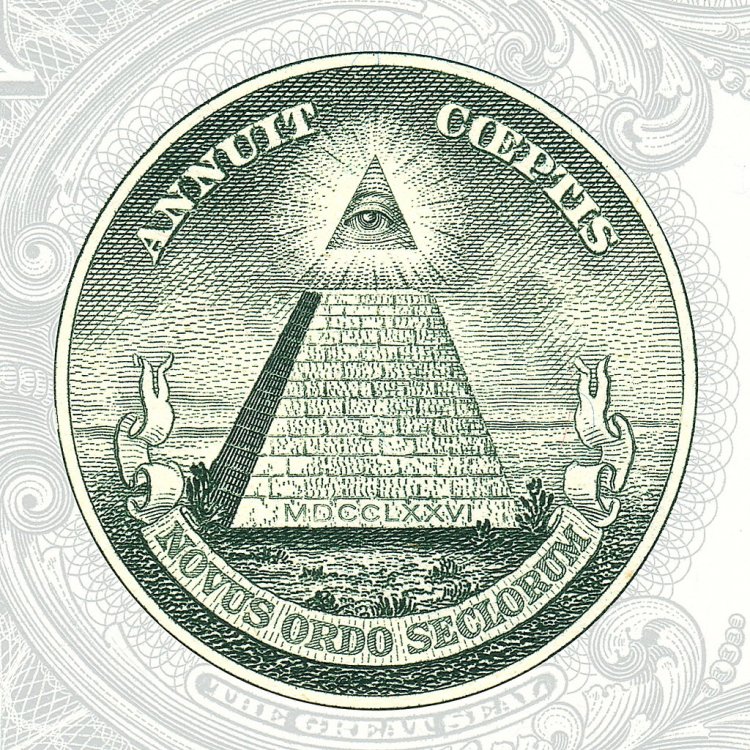

Annuit Cœptis ‘He Approves Our Undertakings’

When you buy Guston’s ‘Arm’ painting for $5M you are buying all of these moments. A man’s life- a shorter one than it should have been, Guston died at 66- condensed into one canvas. Oil paint dripping down the canvas, tears of rage, sadness and pain mixed with pure joy and delight at the possibilities that occur through collisions of paint on canvas. When you take your new Guston home and someone hangs it for you, triumph will be writ large on your wall. This is bigger than life. Or you might hide it in a darkened bank vault, a pyramid for would-be emperors, and let the clock tick tock while you watch the dollars pile up before your widening eyes.

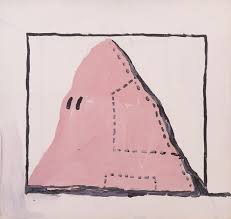

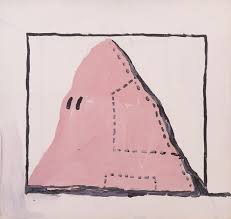

In the painting ‘Pyramid and Shoe’ The artist / worker’s boot stands in opposition to the orthodox structure of the pyramid- a hood. The boot is holding itself back, ready to kick down the pyramid in a moment of visual tension so powerful that it fizzes. Each one of the $5M dollars that you will have had to diligently accumulate to buy Guston’s ‘Arm’, by hook or by crook, contains the sweat of the working man and woman. At the bottom of the pyramid is the immigrant worker- the junkman Louis Goldstein- cash only, zero hours contract, no worker’s rights- taking the full force of the bricks flung their way as they shore up the fabric of society with those very same bricks, digging tunnels, canals, railroads and bank vaults.

Pyramid and Shoe 1977 and Untitled ‘Hood’ 1976

Zero contracted to invisibility nowadays, the domestic worker, nanny, bus driver, construction worker, burger-flipper, cabbie and take-away driver are still grafting in every corner of the city. Krazy Kat’s mantra is the unspoken thought of every immigrant worker punching the clock on the site of another working day:

‘They sure knew what they was doing when they brought me here’

Untitled 1969 37×40 inches

The pyramid/hood is eternal and impenetrable, keeping secrets and approving undertakings as it sits shrouded in mystery.

Peering from the slits in his hood Guston sees through it all and flings us back a truth so blinding that you might just have to turn your head away from your new acquisition and cover your face.This is the kind of truth that makes men build walls to hide behind. Guston gives us freedom from the secrets and lies we cover ourselves in just to get through the day, a dose of revelation into the illusion of our fragile worlds. A shot in the arm.

The Painter 1976 188cm x 295 cm

Novus Ordo Seclorum ‘New World Order’

The dollar bill in your pocket is pure Guston – a giant eye atop a pyramid with the words ‘Novus Ordo Seclorum’ or ‘New World Order’ written below. Pull one out of your wallet and look again at the image through Guston’s eyes. This time the pyramid becomes a hood with one all-seeing eye.

Inscribed above the pyramid is the Latin motto ‘Annuit Cœptis’ or ‘He approves our undertakings’. Of course he does you schmuck, you’re building His pyramid. He’s watching you all the time so go put your hood on and stop clock-watching, you Stumblebum.

Mandarin Stumblebum Guston is handing us a brick. Chuck that brick. He too approves your undertakings with an open hand painted on a canvas and nailed to a wall in an art fair, forever frozen in free fall.

Pyramid featured on a dollar bill

‘Our Laughter Is Muted By Their Agony’ by Charles Bukowski

as the child crosses the street as deep sea divers

dive as the painters paint-

the good fight against terrible odds is the vin-

dication and the glory as the swallow rises toward

the moon-

it is so dark now with the sadness of

people

they were tricked, they were taught to expect the

ultimate when nothing is

promised

now young girls weep alone in small rooms

old men angrily swing their canes at

visions as

ladies comb their hair as

ants search for survival

history surrounds us

and our lives

slink away

in

shame

From: You Get So Alone At Times That It Just Makes Sense, Black Sparrow Press 1989

Sleeping 1977 215 cm x 177 cm

James Gray

17th October 2019 9:44 am

This is so interesting, a wonderful insight into Guston’s world and the social function of the artist. Thanks.

Ed Gray

17th October 2019 9:52 am

Thanks Jim much appreciated. What an inspiring painter.

James Gray

18th October 2019 9:51 am

Some further musings, as Arm was on my mind yesterday. I suggest that the painting is a kind of self portrait from which the artist has largely withdrawn himself, except for his arm and hand. Why has the artist just painted his arm? It’s not a conventional self-portrait. i.e. it isn’t a representation of the artist’s head, face, shoulders, or body. It’s just an arm. Why is the arm emerging from the right side of the painting, reaching to the left side? If the arm were reaching down from the top of the painting or reaching up from the base of the painting it would suggest landscape, an arm, not the artist’s arm, descending from the sky (as in the painting The Line) or an arm emerging from the ground. if the arm were extending into the painting from the left side, I suggest that this would imply that the arm was not that of the artist but of another person. As it is the portrayal the arm asks us to imagine the painter who is attached to it, extending it and painting it, observing it and considering that particular placement for it’s extension from right to left. You can feel that the painter is just beyond the right hand side of the painting, holding up the arm to observe it. Conventionally we read left to right so that our eyes take in the hand first with its outstretched fingers and move along the arm up towards the edge of the painting seeking more, wondering what body lies beyond. Then our eyes move back down the arm and out to the fingertips and it makes me think that along with the painter’s eyes which we don’t see (but which are of course looking and painting this painting) the arm is that other essential tool of creativity. Hand to eye. The tips of the fingers are red suggesting the tip of a paint brush and perhaps the tip of Guston’s cigarette. This is a working arm. The arm extends into the painting and offers to share its humanity, extending a hand to be grasped. The painting is a sign, a hand signal to much more.

Ed Gray

18th October 2019 10:23 am

Lovely Jim. Yes I think it’s all of that. He’s reduced painting down to one symbol- the arm- and that arm is a signal to so much more of Guston’s vision that is not depicted. In the act painting so much of what you do is to remove what is there. The spaces in between are more interesting than the forms often. That’s where the light comes in.